His words were very kind and I can only gabble 'thanks' in return, as well as urge others to visit his blog.

One rather pertinent subject to climate change is that of climate cycles, large shifts in the Earth's climate occurring over several centuries in the short-term and several tens of thousands of years on the more long-term basis.

These shifts cycle between warming periods and cooling periods, normally to an extreme extent (as much as 6 degrees Celsius from the mean), and we are currently in the middle of a warm period.

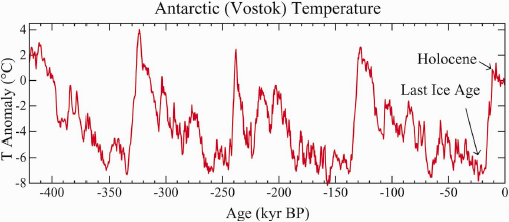

A graph of the natural cycles

Warming cycles are often held up as a disproof of anthropogenic global warming theory.

However, this is misunderstanding a basic principle of the theory of man-made climate change; not that the temperature is at the highest it has ever been but that the rate of change of temperature is higher, which can be much more dangerous (compare slowly easing oneself on to a bed of nails and then dropping on to it from a height of several metres).

The Earth and its ecosystems can adapt to extremes, given time. They cannot adapt well to large changes within a short amount of time, as the dodo faced when humans along with the things which humans brought (cats).

So, back to its supposed status as a disproof.

There are many misunderstandings concerning climate change. One of those is the idea that proponents of the theory claim that temperatures today are the highest they've ever been and then hold this up as evidence of warming.

This is wrong.

It is claimed only that the current rate of change is at an unprecedented high1; 0.76 degrees Celsius in a century and a half.

And this, as far as we know, is an unprecedented rate. The Vostok data doesn't show anything this rapid. The EPICA data doesn't.

Neither do tree rings, sea shells or any other common long-term temperature proxies.

The current warming could be part of a natural cycle, although we should really be cooling or at least remaining stable at this point in time.

However, the rate of warming leads us to believe that this may not be the case.

References:

1. http://www.global-greenhouse-warming.com/global-temperature.html

The graph was produced by myself using the Vostok ice core temperature data.

It uses a reversed axis for time (the present is on the left) and, due to some quirk of OpenOffice.org Calc, changes in time-scale further back (something which I'm currently trying to fix).

It is necessarily shrunk to fit on the page.

The mean is approximately 4 degrees below the modern value of -55.5 degrees Celsius (remember, this is Antarctica).