Many of you will have seen Al Gore's An Inconvenient Truth and Martin Durkin's The Great Global Warming Swindle, probably leaving you confused over whether man really does have anything to do with global warming or not.

The official answer: no-one's really sure.

The real answer: probably.

The first incorrect answer: definitely.

The second incorrect answer: definitely not.

Double the incorrectness if the 'definitely not' is followed by conspiracy theory rambling.

The main reason that man is suggested as a cause is due to his greenhouse gas emissions.

Humans and human industry emit thousands of millions of tonnes of various gases each year, considerably affecting the composition of the Earth's atmosphere.

As an example, carbon dioxide, the most commonly cited of these emissions, is up to a concentration of 385 parts per million (ppm)1, or 385 molecules of carbon dioxide in every million molecules of the Earth's atmosphere (or,alternatively, 0.0385% of the atmosphere).

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, when human industry began to grow in earnest, the levels

were around 280 ppm (and had remained below 290 ppm for at least 400,000 years prior to today)2.

Methane, another commonly cited emission, has grown by about 150% since 1750,

around the beginning of the early Industrial Revolution. It is, however, still present in much smaller quantities than carbon dioxide (approximately 1,750 parts per thousand million (ppb) in 1998)3.

Several gases that we emit are categorised as 'greenhouse gases', gases which retain heat radiation from the Sun in our atmosphere.

Naturally occurring greenhouse gases keep our planet significantly warmer than it would otherwise be, making it suitable for life such as our own.4

It has been shown that greenhouse gas concentrations remained relatively stable for several hundred millennia, although when we go back further we see that there were much higher concentrations in the atmosphere than today.

In particular there were extremely large amounts of carbon dioxide and, more importantly, methane, in the atmosphere around the time of the Permian extinction event, approximately 250 million years ago.5

There is strong evidence to suggest that the temperatures around the equator increased by five or more degrees Celsius at this time, meaning that temperatures at other latitudes would have increased by higher amounts.6

That these greenhouse gases, which include water vapour, carbon dioxide and methane, increase temperatures on the Earth is undoubted. However, what is disputed is the extent to which additional amounts other than the natural will affect the Earth's present climate.

This may seem a simple question - well, if they increase temperatures, then more will increase them still further, obviously - but it is actually quite complicated.

For one, not all factors affecting climate are known or are understood well enough to produce perfect mathematical models of climate.

Clouds are a particularly big unknown; logically, more are formed when there is a higher concentration of water vapour in the atmosphere, but how do clouds affect us?

At night they appear to retain heat by reflecting outgoing radiation back to the Earth, but at

day they do both this and they reflect incoming radiation from the Sun.7

Which one is dominant? How exactly does the amount of water vapour affect their formation? A controversial one, do cosmic rays affect their formation (the answer seems to be 'not really')?8

Even worse, computers are not powerful enough to answer this for us. The most powerful supercomputers designed for climate models cannot handle anything but cells on the Earth about a thousand times bigger than the average cloud, so any effect has to be guessed at by scientists and an approximation fed into the machine.9

Clouds are not the only great unknown. Also unknown are many things about the Earth's oceanic circulatory systems, which have a large effect on climate. Only the simplest of models for these can be produced, and any inaccuracies are likely to be quite large and will multiply in scale with each time-step as the models are run to predict future climate.

There are many other things which also affect the climate, including positive and negative feedback loops. These will be the main topic of the next post (note how in this post we have not arrived at a conclusion as to whether man is causing any warming. The science of climatology is relatively young as a science and there are too many uncertainties to arrive at any definite conclusion, only probabilities).

References:

1. http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/webdata/ccgg/trends/co2_mm_mlo.dat

2. http://cdiac.ornl.gov/ftp/trends/co2/vostok.icecore.co2

3. http://www.epa.gov/methane/scientific.html#atmospheric

4. http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/7h.html

5. http://www.astrobio.net/news/print.php?sid=582

6. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Permian-Triassic_extinction_event#Methane_hydrate_gasification

7. http://www.giss.nasa.gov/research/briefs/rossow_01/

8. http://environment.newscientist.com/channel/earth/climate-change/dn11651

9. http://www.aip.org/history/climate/GCM.htm

Thursday, 23 August 2007

Greenhouse gases and clouds

Posted by

Daniel

at

18:29

5

comments

![]()

Labels: clouds, extinction events, greenhouse gases

Sunday, 19 August 2007

First, the reasoning

That's what this post will attempt to explain: the reasoning behind the assumption that the Earth is warming.

We have direct measurements of quasi-global temperature going back to about 1850 or so.1

In Central England we have records going back to 1659, the furthest far back instrumental records go.2

From 1850 to about 1940 we measured, on average, an increase in global temperatures; from 1940-1970 a cooling and from 1970 onwards a heating again.3

This can be shown in a graph, like so:

This is a graph from the BBC, by the way; in future I'll try to make my own.

It can be seen quite clearly that, on average, temperatures have increased.

However, climate is a long-term thing; a mere century and a half of data isn't really evidence enough.

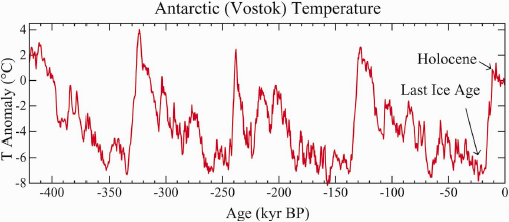

We have indirect measurements of temperature going back around eight hundred thousand years, however, contained in the ice cores of Antarctica.4

Here is a graph showing temperature deviation from the average going back four hundred thousand years.

It was created by James Hansen of NASA.

So nothing special, you might say. Temperatures have been higher in the past than they are now.

Except that we haven't taken into account rate of change.

Within the past century and a half average temperatures have risen by 0.76 degrees Celsius. 5

This is an unprecedented rate.

Something must be causing it, and that's what we'll come back to in the next post.

References:

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instrumental_temperature_record

2. http://hadobs.metoffice.com/hadcet/

3. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instrumental_temperature_record#Warming_in_the_instrumental_temperature_record

4. http://www.esf.org/activities/research-networking-programmes/life-earth-and-environmental-sciences-lesc/completed-esf-research-networking-programmes-in-life-earth-and-environmental-sciences/european-project-for-ice-coring-in-antarctica-epica-page-1.html

5. http://ipcc-wg1.ucar.edu/wg1/Report/AR4WG1_Print_SPM.pdf

Posted by

Daniel

at

13:29

0

comments

![]()

Labels: clouds, extinction events, greenhouse gases, introduction, temperature record, vostok, warming

An introduction

An introduction of some sort is in order.

I am Daniel Rhodes-Mumby, a fifteen year old student at Caistor Grammar School in Lincolnshire, England.

I first became involved in political issues at the age of about thirteen, and global warming at about fourteen.

In the two years that I have been involved in politics, I have changed my views quite radically. Originally I was a conservative; then I became a communist, before gradually moving down to socialist.

I am now a moderate liberal, in the sense that I support a person's freedom to do whatever he wants as long as it doesn't harm anyone.

As a combatant on the bloody fields of political argument, I have learnt a lot, in particular how to listen and how to fight. I have been on the wrong end of insults and abuse; likewise, however, some of my opponents have been. I have never promised perfection, and I have a somewhat short temper at times.

I first learnt about the greenhouse effect when I was eight years old or so; I found the concept interesting, but nothing to worry about.

Learning a bit about global warming in Year 9 of school, I sought to learn more. I searched on the Internet, in magazines and in encyclopaedias.

Since that point, I have been a keen proponent of the theory of anthropogenic (man-made) global warming, and I have been involved in some fairly fierce arguments over the matter.

My reading of scientific papers in recent history, coupled with my own limited research in the field, has convinced me that anthropogenic global warming is, at the very least, likely to be the truth.

My research will be publicly available on this blog, and I can e-mail it to anyone who wishes to see it at any time.

In addition, I am collaborating on a research project with several other people which I will keep you informed about.

Why am I telling you all this?

Simple.

I won't pretend to be a fence-sitter. I'm a proponent, and this blog will be tainted by that, although perhaps tainted is not the word.

However, I give my promise that I will try to be as unbiased as possible, and that if you - that is, anyone who wishes to debate over something - are courteous to me, then I will likewise be courteous to you.

I will never throw the first insult in a debate, and I try not to throw any at all, although sometimes I weaken and do so in retaliation.

The purpose of this blog is to inform people about global warming and the theories surrounding it. It should also inform people about the uncertainties in the climate change debate; how we have probabilities as opposed to certainties, how sometimes the physics is uncertain, how models of climate are not necessarily accurate and how it is impossible to prove anything in science.

Global warming fills these pages, but it is as much a blog dedicated to science as a whole.

Posted by

Daniel

at

13:00

0

comments

![]()

Labels: introduction